WordPress database error: [Table 'adding_b51201.wp_SBConfiguration' doesn't exist]select * from wp_SBConfiguration where id='1'

Welcome to Module 3.1 Return to Dashboard

Module 3.2

Module 3.3

Different communication skills work in different situations. Learning communication skills is no help unless you also learn when to use which ones. Does that sound useful to get clear on?…

One interesting question to ask any time you are talking, or spending time with another human being is, ‘Who here is not feeling happy right now?’

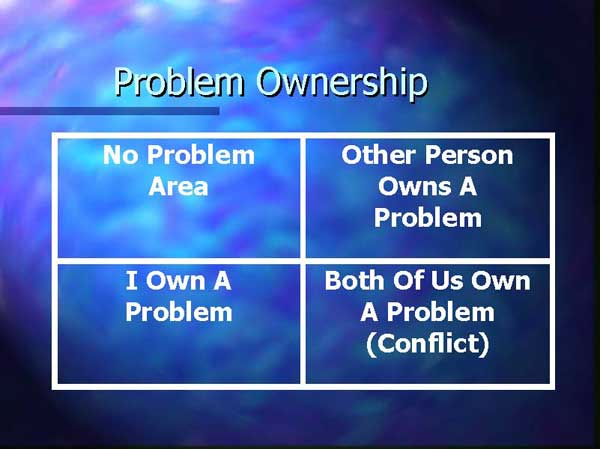

If the answer is ‘no-one’, that’s great! In that situation no-one owns a problem, to use a new piece of jargon. If the answer is ‘me’, then I own a problem, in this sense. And if the answer is anyone else, then the other person owns the problem.

This way of understanding situations was developed by Doctor Thomas Gordon, author of P.E.T. Parent Effectiveness Training and many other books. Notice that this way of using the words ‘own a problem’ is different from the way many people use the phrase.

For now, I’d like you to get used to this new way of thinking about it. When I talk about someone ‘owning a problem’, I don’t mean that it’s their fault, and that they should fix things up or anything like that. I mean that they are the ones who are not feeling happy about things. They are the ones who feel angry, hurt, sad, frightened, resentful, embarrassed, or otherwise unaccepting of the situation.

Let’s say your teacher enters your class and tells you, ‘I’m very disappointed with you all. You’re not getting through this work quickly enough. You may be enjoying yourselves, but you’re really not treating this seriously enough’.

Now, who ‘owns’ this problem? The question, restated, says who here is feeling unhappy right now? The teacher is, so the teacher owns the problem. That doesnt mean it’s her fault, or that she’s the one who has to fix it up: just that she is the one who is upset.

Let’s take another example. As you arrive at your work, you see a young man with a spray-can of paint writing slogans over your workplace walls. He’s singing to himself as he writes. In ordinary language, we might well say, ‘That guy has a problem’, but in this new way of using the phrase, he probably doesn’t. He’s having a great time, painting the walls and singing. Who is feeling unhappy right then? Possibly you are! It’s not your fault, and it doesn’t mean you should clean it up. All we’re saying is that it is very important to work out in any situation: Who is unhappy about this?’ That’s more important to understand than ‘Who is to blame?’ or ‘Who will have to fix this up?’

Sometimes people say: ‘Well, the guy painting the walls may not own a problem now, but he sure will once I finish with him.’ That may be true. What we’re doing here is checking who is feeling unhappy right now.

So sometimes in everyday speech we’d say ‘That person has a problem’, when by this way of thinking, they don’t. And sometimes we’d say There’s no problem’, when in our special sense there is!

Here’s an example of this: Your friend tells you he’s lost one of the handouts from a course you’re both doing. He say’s he’s really worried about asking the tutor for a replacement. You think he’s getting worried about nothing. Does anyone own a problem? In the sense we’re using it, yes. If your friend is worried, he’s worried. It doesn’t matter how trivial it seems to you. What counts is: Who is feeling unhappy right then?

There’s a good reason for working out who ‘owns the problem’. The ways of talking which will help when another person owns the problem (helping skills) are very different to the ways which help when you yourself own the problem (assertiveness skills, problem-solving skills). And as you may have realised, there will be times when you both own a problem (such as when you and your friend both want to use the same textbook at the same time). Those situations, called conflicts, require a third set of skills (conflict resolution skills).

I have another reason for wanting you to know about problem ownership though. That is to explain to you my role as the instructor of this seminar. It’s not my job to tell you when you should or should not own a problem. I don’t intend to tell you which things you should feel accepting of or which things to be upset about.

But once you have worked out what you want from your relationships, the skills we’ll practice will help you achieve it. What you want is special to you. Your dreams for your life may be different to anyone else’s, and what ‘gets on your nerves’ may be totally different to what ‘gets on someone else’s nerves’. That’s why my invitation to you is to use this course like a supermarket of new choices. Only you can know what choices will work well for you in which situations. If what you’re doing already works perfectly, I’d say go for it! If it leaves you or others around you feeling less than delighted, this course contains some new possibilities.

Because you are human, you will want different things at different times. Have you ever had one of those days when you wake up and realise you’re half an hour late. As you rush your clothes on, it occurs to you that you’ve double booked yourself later in the day. Your bike or car has a flat tyre when you get to it. And as you head out the gate towards the bus stop, you grab the mail from the mailbox… and find the electricity suppliers are going to cut off your power if you don’t pay that bill you thought you’d paid last month.

On this particular day, when your friend at work says, ‘I can’t pay you back that $100 I owe you this week, sorry’, you may own a problem!

Let’s take another day though. You wake up fully rested. As you’re getting ready, you receive a phone call from an old friend. They’re coming over to visit tonight and you’re really looking forward to that. As you’re leaving you check the mail and find your tax return – the Inland Revenue Department are giving you back almost double the amount you expected. So, now, you go to work and your friend tells you about the $100. Probably it’s not a problem.

People are not machines. At different times they feel differently. A behaviour that is no problem when one person does it may have you ‘own a problem’ when someone else does it. A behaviour that is no problem at home may be a problem at work. What counts is how you feel right now.

By the word “behaviour” we mean something you can see, hear or touch. It is a sensory specific description of what actually happened; without any judgements, or guesses about what the person was thinking. If I stand on a chair while teaching you, “The instructor standing on a chair while talking” is a sensory specific behaviour. “The instructor being arrogant” or “The instructor thinking they’re better than us” are judgements, opinions or guesses. So the word “behaviour” is used in a very exact sense here.

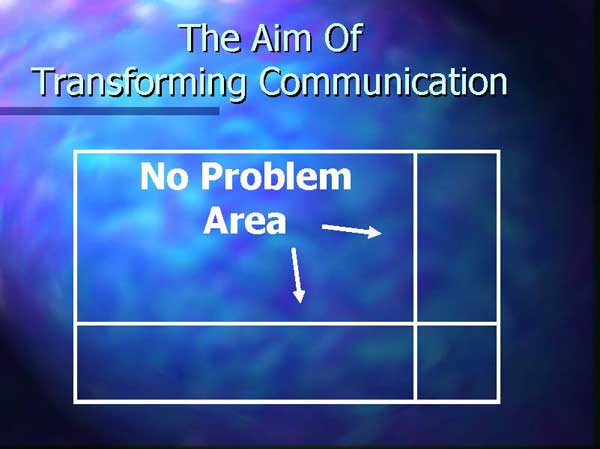

The aim of the skills you’re learning here is to be able to expand the area of your life where no-one ‘owns a problem’; the No-problem area. You could think of it like this:

To practice your understanding of these concepts, turn to the Problem Ownership page in your workbook, and answer the questions there. There may not be one “right” answer because different people will find different things a problem For example, some people are “always” upset to discover that someone close to them is unhappy, whereas others might want to help, but not feel upset about it.

It is important to note that where both you and the other person own a problem, you do not own the same problem. Often people assume that if both they and the other person are upset, they must be upset about the same thing!