WordPress database error: [Table 'adding_b51201.wp_SBConfiguration' doesn't exist]select * from wp_SBConfiguration where id='1'

Welcome to Module 6 Return to Dashboard

Module 6.1

Module 6.2

Welcome back for the sixth module. In module 5 you learned that people think using their senses, visual, auditory, kinesthetic or auditory digital. And as they get information from their memory or imagination, their eyes move. People will also match these senses with the words they use. For example somebody would look up and say “The way I see it…” (that would be visual), or they would look down to the right and say “It feels to me like…” (that would be kinesthetic).

Everything you’ve learned so far, such as rapport (module 2) and attending skills, open questions and reflective listening (module 3 and 4), and matching sensory systems (module 5), can be used in communications where the other person owns a problem and you want to help them finding solutions.

This module will deal with the situation where you own a problem and would like someone else’s behaviour to change.

One of the original change agents studied by the developers of NLP was Virginia Satir. Satir is sometimes called the Grandmother of family therapy. Before her time people working with disturbed children or teenagers would just see the child, and then send them back into the same family. Satir developed the idea of working with the whole family.

All of the skills you’re learning on this course were skills Satir used in her work. When she was a child, Virginia lived in what would now be called a dysfunctional family, with an alcoholic father and so on. Virginia spent much of her childhood in hospital, with a variety of problems. When she was five years old she set her life’s course by deciding that she wanted to be “a detective investigating parents on behalf of children”. And so that became her work, as a teacher and social worker.

After the Second World War, she worked for some time with survivors of the concentration camps. These were people who had been forced to witness and do horrific things. One time Satir was counselling with a woman who had put children to death by putting them in a furnace. And also a lot of Virginia’s job involved reflective listening and helping this woman clarify her goals.

An adoptive parent herself by now, Satir began to dread seeing this woman. Satir herself had a problem, thinking about what the woman had done. For some time she agonised over what to do about this. Here she was, supposed to be helping this person, but she herself was feeling angry and distressed at the woman. Which is of course a situation many parents, many teachers or counsellors will find themselves in sooner or later. The question was, was it right for her to say something? And if she did, how would she explain her concern, knowing that this woman might have her own feelings of upset about the issue.

This is a different situation to the one we’ve been dealing with so far, where only the other person has a problem. When I have something I need to explain, again there’s an art to explaining it successfully. So would it be useful to get clearer about how to do that most successfully? How to explain my concern when I own a problem?

The situation where I own a problem includes times when I feel angry about what someone else did or said, where I have more work to do as a result of how things are happening, where I feel hurt or afraid or upset, and so on. This situation requires a very different stance to the situation where I’m Okay and just aiming to help the other person. When I own a problem, I have four main aims with what I say:

My Aims When I Own A Problem

- I want to get the situation to change

- I’d like to ensure that similar situations are less likely to happen in future

- I want to preserve the relationship between myself and the other person, so they’ll co-operate with me in future

- I want to preserve their self esteem (if nothing else because people who feel bad about themselves are harder to live with!).

Interestingly, there are several ways that people respond to this situation that are less than helpful. To demonstrate this, think of a situation where I as a seminar leader might own a problem with you as students, such as participants arriving late, people not doing the home tasks at all, people missing sessions, people bringing their pet alligators to class etc. Think of this situation as you read these Roadblocks, this time as people tend to use them when they themselves own a problem:

- Ordering “You people had better stop… now. Okay!!!”

- Threatening “So help me, if you ever again…. you’ll be out of this seminar before you can blink!”

- Moralising “You’re old enough to….”

- Advising “Okay, to help you change this behaviour, here’s what you should do….” (suggest something fairly absurd, but vaguely related to the problem)

- Lecturing “You know, I was reading some research on that the other day. It said….” (make up some research suggesting that the problem behaviour is linked to disastrous results).

- Blaming “There’ll be no-one but you to blame when you fail in this seminar. It’s your own fault for….”

- Labelling “I have never met such a selfish, insensitive group as you!”

- Analysing “The real reason you’re… is because you know it upsets me, isn’t it. You’re just trying to get at me. I’m not fooled.”

- Praising “Now look; I know you’re generally co-operative students. And so I’m sure there won’t be any more… .will there?”

- Reassuring “You poor things. You must be having a hard time, to be….”

- Probing “Do you always act like this? Is this the way you think mature seminar participants behave? Do you treat people at home like this?”

- Sarcasm “Go right ahead. Don’t worry about me! Just carry on ignoring my feelings. Is there anything else you can think of that would make life difficult for me?”

So how was that? Familiar? Many of these are put-downs. Many of them say I don’t think you’re caring enough or intelligent enough to co-operate with me. Others are just so indirect you’d be lucky to work out what I want you to do at all! The interesting thing about all those roadblocks used in this situation, is that every time I’m saying something about you. “If you ever…”, “you should…” And yet its me who owns the problem!

If I really want to achieve my aims of getting change, preserving our relationship and so on, I’d be far better to focus on what my problem is, to send an I Message. The more information you have about my problem, the better able you are to understand why I’m concerned, and what your choices are to change. There are three key pieces of information I could give you:

I Message:

- Sensory Specific Behaviour

- Concrete Effects

- Feeling State

Okay; get a piece of paper and a pen, or get a blank page on your computer and write down one situation you know of where you’d like to send an I message of this sort. So you’ve got an example to think over as we go into this more fully. Choose an actual situation that’s happened to you, perhaps a situation that will happen again (like someone not tidying up in a shared space, or misusing your things), a situation that’s useful to learn more about.

Firstly, the actual sensory specific behaviour of yours that I’m having a problem with (and remember that phrase “sensory specific behaviour” means exactly what I can see, hear or physically touch, rather than my opinion or judgement about it). “Participants being insensitive” is a judgement. “Participants arriving ten minutes late” is a behaviour. “Arriving home at some unbelievable hour and crashing through the house loud enough to wake up the dead” is a judgement. “Arriving home around 1am and shutting the door loud enough so I woke up” is a behaviour. “Never bothering to get work ready on time” is a judgement (it makes a guess about whether I bother). “Leaving that report on my desk four days after we arranged for it to be there” is a behaviour.”

One simple way to check that you’ve described the behaviour in a sensory specific way is to ask yourself “Would the other person agree that this is what actually happened?” For example, it’s probably not worth telling someone that they “never” do such and such, or they “always” do such and such. They can usually think of a counterexample. Like “Well I remember one time last year I got a report in on time”. It’s not worth wasting time arguing about whether it’s “never” or just “this time”. Also, avoid words that guess what the person’s intentions were. Like “You deliberately arrived late” or “You purposefully ignored me” or “You selfishly went home early”. Your aim is just to tell the person what happened that was a problem!

Secondly, any concrete effects that that behaviour results in; like me having to do extra work, lose money or time. These need to be actual physical effects. “When you arrived home late, I got so worried I nearly died” is probably not a concrete effect. “I spent a quarter of an hour phoning up people to find out where you were” could be. Also, effects on someone else don’t count here, sorry. “When you got the typing in late poor Mr Jones had to stay half an hour later to collate it” tends to provoke a response like “Well maybe he needs to talk to me about it.” The aim is to solve my problem, and that’s what this skill works for.

Sometimes there is no concrete effect, you still have a right to send an I message! Situations where you own a problem with someone else’s behaviour, but it doesn’t concretely affect you are called values conflicts. Examples are “I don’t like your clothes style”, “I don’t approve of your ideas about women’s rights”, “I’m worried about you taking those drugs”. Again, the best way to check your concrete effects are sensory specific is to ask “Would the other person agree that this is a real result of what you do?”

Thirdly, the feeling state I get in as a result of that. This is an extremely impactful and important part of the message. Now this is interesting too. Because you’ve heard people say things like “Well, I feel that you’re a selfish slob”. And that isn’t quite what we’re after here. Feeling states are not the same as beliefs or opinions.

To say ‘I feel she’s putting pressure on me’ is not actually describing a feeling state. It’s describing a belief about what ‘she’ is doing. As a simple test, if the word ‘that’ is or can be put after the word ‘feel’ in your sentence and it still makes sense, you have an opinion or belief. For instance: ‘I feel you’re being rude’ is a belief, because ‘I feel that you’re being rude’ still makes sense. ‘I feel lonely’ is a real feeling, because ‘I feel that lonely’ loses the sense of it. ‘I feel I’m a good loser’ is a belief, because ‘I feel that I’m a good loser’ still makes sense. ‘I feel like jumping for joy’ is a feeling, because ‘I feel that like jumping for joy’ is not correct English.

So for example, in the situation you read the roadblocks for before, what is the behaviour ? Go through them again and describe them in sensory specific terms.

And what, if any, are the concrete effects of that on me?…. And how do I feel when I cope with that behaviour and those concrete effects? To write an I message, one simple way is to use this format:

When…(behaviour)… the result is…(concrete effect)… and I feel…(feeling)

For example, “When you don’t turn up for an appointment we’ve made, I end up not being able to use the time I’ve put aside, and I feel resentful.” It’s not necessary to use the word “feel” of course. If you work with people who are strongly auditory digital, they won’t grasp the point anyway. You can simply say “I resent it”. In reality, you can vary the format several ways.

You can put things in any order. You can say “I resent not being able to use the time I put aside for your appointment” (that’s feeling, then effect, then behaviour).

Some people ask ‘Shouldn’t I suggest the actions I’d like the other person to take, the solution?’ Our experience is that solution suggesting is only helpful when the other person resists acting because they have a problem of their own. This situation is a conflict, and we’ll explore it later. Suggesting solutions in your first I message runs a high risk of leaving the other person feeling cornered, insulted, and ordered about. It’s as if you said ‘Im going to spell out step by step what you must do to solve my problem, because you’re too dumb or too selfish to understand’. You’re quite right that often an I message won’t solve your problem instantly. It’s not the complete answer— that’s why there are more modules in the course!

So now, turn to the I Message worksheet in your workbook, and take the time to write an I message following these principles. Check that the behaviour and effects are sensory specific, that the feeling state is actually a feeling state, and that there’s no hidden “you” message or solution added.

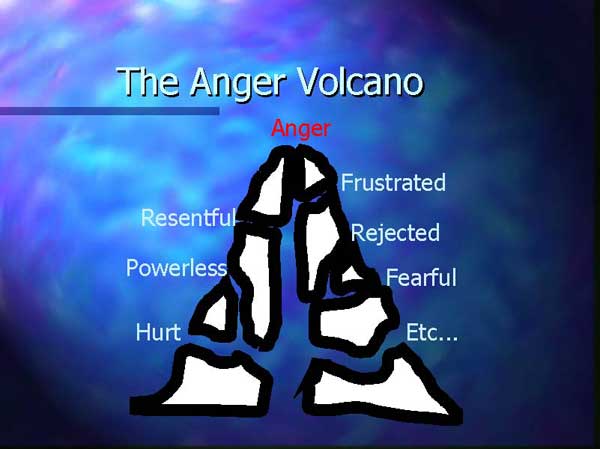

Now, there’s one more thing that’s useful to know about the feeling part of your I message. Sometimes people, in describing the feeling, use a word like angry, annoyed, furious, ticked off or some variation on that. We find that’s pretty common. And there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a great I message. To have more impact in terms of getting change, though, it’s useful to notice that the word “anger” tells you that there’s force to the feelings, but it doesn’t tell you so much about what the feeling is.

Harriet Goldhor Lerner, in her book The Dance of Anger, says that while feeling angry alerts us to the fact that we own a problem, and gives us the energy to do something, it does not in itself explain what the problem is. This is why Lernor suggests that, rather than giving vent to anger, we need to feel it and discover what the problems that cause it are. Recognising the feelings which produce the anger signal means you can send even clearer, more concrete I messages.

Let’s say you’ve arrived late for your seminar. The trainer sends you an I message: ‘I feel really angry when you arrive so late.’ The message tells you about the force of her feeling, but it doesn’t actually tell you what she feels. Compare it with an I message explaining ‘I feel really worried about whether I’m going to get through the material when we start so late’ or ‘Im getting very frustrated with having to stop and start so often’.

It’s easier to want to help someone who is ‘worried’ or ‘frustrated’ than someone who is ‘angry’ because

(a) you know more about what’s causing their problem

(b) you can hear the feelings as inside them rather than about you.

A father who has trouble with his kids running round the supermarket while he’s shopping will get a better response by explaining ‘I feel embarrassed about the people staring at me’, rather than ‘I feel angry at your running’.

Transforming Communication instructor Bryan Royds suggests that anger can be thought of as the top hole in a volcano. Usually the volcano has side vents and when pressure builds up lava runs out these side holes – holes like frustration (the feeling of being blocked), fear, embarrassment, resentment (the feeling of doing more than a fair share), pressure, rejection, and powerlessness. When these feelings aren’t expressed, the force which was behind those feelings doesn’t just go away. It builds up and finally explodes out the top. Someone who is constantly angry needs to re-open the other vents so more appropriate feelings can be expressed. This is what I messages do.

Think about what other feelings lie underneath anger in your personal volcano. Think of situations where you get angry. What other feelings are likely to be there at those times?